In Des Moines, Iowa there is trouble brewing for agricultural farmers of all sizes. The claim? That water run-off from farms — even family sized farms — with drainage tiling cause water pollution. But, as most of life issues go, this one is not as simple as you’d think. Drainage tiles are necessary for food production and, in urban environments, can save the foundation of a house.

However, farmers have known that when you drain away the soil water, you also drain away the nutrients . They often tried to balance this with using less fertilizer if they knew it would be washed away, wasted, and polluting the environment. (Despite what some think, no farmer wanted or wants to pollute the land that gives them their livelihood and ability to keep a roof over their head, clothes on their back, and food on the table.) Now, as we gain numbers and see the very long-term environmental effects, both farmers and non-farmers are trying to undo all the damage that had been done in the past by ignorant people.

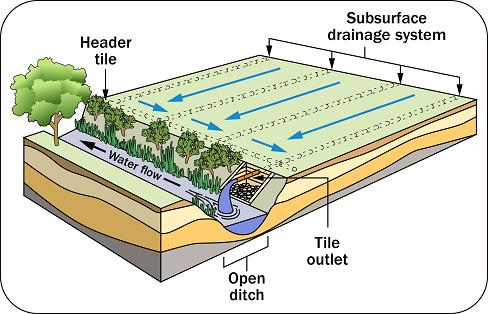

What drainage tiling does and how it’s used

Drainage tiles are not new technology; they have been used since at least 200 B.C.

If the land is wet, it should be drained with trough shaped ditches dug three feet wide at the surface and one foot at the bottom and four feet deep. Blind these ditches with rocks… Then dig lateral trenches three feet deep and four feet wide in such a way that the water will flow from the trenches into the ditches. — Marcus Porcius Cato, Roman Farm Management

This old methodology has saved countless farms from flooding during unpredictable storms, kept the population fed, and the owners of the land making a living. This is all by adding a layer of some permeable material that that excess water can flow through, but the soil and roots stay on top where they can thrive.

It’s a simple, yet elegant solution that has been modernised by the types of materials that are used help protect the land at the same time allowing agriculture to be more efficient. Despite the change in materials from clay tiling that changes the soil compaction to sturdy, environmentally sound PVC and other materials, there were still problems. The roots would damage the drainage system, nutrients would run off, and you had to be more careful about soil compaction lest your crops be stunted from lack of aerated soils.

With the 2010 Journal of Environmental Quality published paper stating the nitrate levels of Mississippi River, it really hit home to the world how bad the nutrient loss was, and how damaging the nitrogen loss was.

We finally understood the full impact of all those nutrients lost, primarily in the Gulf of Mexico where algal blooms were becoming more prevalent, choking out natural fish wildlife. Even back then, though, it was noted that it’s not that simple. The nitrogen from the effluent of people plus agriculture all created this. Despite the crop rotation and other methods of naturally holding onto the nutrients locked in the soils, there was no clear picture where it all came from and lead to.

Still, as the article at Phys.org quotes, the solutions were far trickier.

“Until we change the payment system beyond our focus on yield alone, we’re not going to make much progress in reducing nitrate losses. We also haven’t developed voluntary programs that really address nitrate loss from tiles, and we need to provide more incentive and cost-share funding to producers. We may also need regulation. We could say to producers, if you buy fertilizer, you’ve got to do one of these five things,” [Mark David] said. “There’s no one solution.”

Farmers, agricultural societies like FFA, and the local governments worked together to come up with voluntary solutions to try out along accompanying government facilities that would help trap and scrub nutrients from the water. That is where we are at today, testing the various solutions at a volunteer basis and working hand in hand with local governments to clean up the mess we all made in our zeal for efficient agriculture to produce affordable food.

Run-off can be controlled, not just filtered.

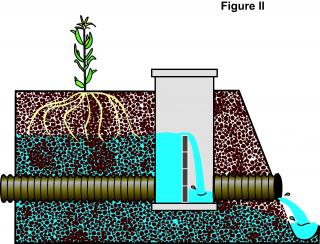

Run-off water used to be filtered at a facility, but “new” technology has been taking off for 2 years that allows farmers to control the drainage in situ, allowing for the run-off to be lessened. This irrigation equipment goes on the end of a drainage line to regulate the water going out at different times of the season, depending on needs.

According to the University of Missouri Greenley Memorial Research Center, the system shown to the right can reduce nitrate and nutrient loss up to 75% simply by storing the water throughout the summer when the crops are in need of fertilization and water. This both decreases the amount of fertilizer needed over all for the crops, and reduces the amount of nitrate accidentally released in run-off significantly.

This subterranean irrigation mode uses 25% water than the overhead irritation sprinkler systems as well. It sounds like a win-win, doesn’t it? If so, why isn’t everyone using it?

Well, first of all, it’s only about two years old. It takes time for farmers to get money to implement new technology, and with the drought the last few years, it’s been nearly impossible. To make matters worse, crop insurance doesn’t pay out for 2 years after the bad crop yield. That puts us right at the first year farmers have been getting crop insurance money back.

This makes the Des Moines litigation is premature.

Farmers have been struggling to make a negative feedback loop to halt and reverse the nitrites that were free flowing into the water supply. The article mentions that 90,000 farmers had 18 months and have spent lots of energy and money redefining and implementing conservation practises such as conservation tillage, high-tech fertilizer applications and added conservation practices such as cover crops. It takes time to see a feedback loop take hold, and in little more than a year is barely time to register any change. And, while there are indications that the nitrates and other nutrients are dropping, it is slow going before they can implement better technology — and to do that, they are waiting on their insurance checks to afford it.

As an urban farmer in the U.S., the decision may impact you as well.

Whether you live in a house or an apartment, your effluence drains from your bathroom into the sewage system, which goes to a water treatment plant. Even if your sewage didn’t go straight to a treatment plant, it wouldn’t make much of an impact.

Whether you live in a house or an apartment, your effluence drains from your bathroom into the sewage system, which goes to a water treatment plant. Even if your sewage didn’t go straight to a treatment plant, it wouldn’t make much of an impact.

Your garden, however, can. And, if you live in a place where you have standing water, you may be subject to any rulings passed down from the EPA and Federal courts. Even a small puddle would be property of the Department of Natural Resources, and thus subject to their rules and regulations.

While this sounds like I should put a tin foil hat on, I assure you it won’t affect small households that grow food for only themselves. It will likely only apply if you try to turn it into a business of any sort, such as selling your fresh crops at Farmer’s Market or homestead goods on Etsy. At that point, you’ll fall under the small business clause and be subject to all the Federal mandates and rulings.

If you would likely fall into these categories, then be at ease because you can likely regulate your own nitrite levels by using more natural fertilizers, such as compost, kelp and bone meal as needed. Follow this by also making sure your basement, garage, and storm drainage systems are all in efficient functioning order to keep run-off from being a problem, as per this post from Reliable Basement Services.

Frankly, it’s easier to self-regulate on a smaller scale because these more natural fertilizers are easier to use on this scale. Plus, we can more easily control our nutrients, only applying them when absolutely necessary, thus avoiding adding any more nitrates to the environment while also staying under any likely Federal ruling to come.

References: